Dear Abigail: Excerpt

CHAPTER XVIII

“As always I hope for the best”

...

Abigail’s journey to Washington D.C. was as much a leap into the unknown as crossing the Atlantic. She traveled with only servants. John had left Peacefield two weeks earlier, and her niece Louisa had stayed behind at the Cranch farmhouse. A shocking event had occurred. Mary took sick and was barely conscious throughout the end of the summer. She was now teetering between life and death.

It was the beginning of November, 1800, the weather was bright, the leaves browning, when Abigail left Philadelphia, turning southward. The path was clear, but dreary, a mere tedium of forests, “destitute of natural as well as artificial beauty.”> Baltimore, a thriving town dropped into a cliff sixty miles from the new capital, briefly relieved the monotony, but, it was gone in a flash, and then the woods resumed, unsettling Abigail like the infinity of the ocean. The roads were dilapidated, and bridges vanished so they had to splash through angry streams without a soul to salvage them should the carriage collapse. Worse, eight miles out of Baltimore, after stopping to see the town of Frederic, they lost their way and wandered two hours on dirt roads, pressing down or breaking off tree boughs in order to move at all until at last a black man in a cart appeared out of nowhere and pointed them to the post road. Now thickets resumed, opening every sixteen miles or so to a threadbare village—thatched cottages without glass windows and only a few black faces in sight.

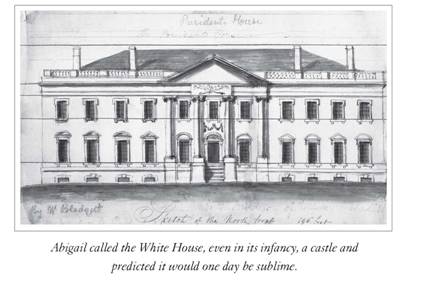

At 1 p.m. on Sunday, November 16, Abigail drove into the capital. “As I expected to find it a new country with Houses scattered over a space of ten miles and trees and stumps in plenty . . . so [it is],” she wrote Mary. Washington was a city in name only, like the “wilderness” she had traversed to arrive. Stonecutters were drilling and bricklayers pulleying their fired clay in a rush to complete the President’s mansion, “a castle of a House—so I found it— . . . in a beautiful situation in front of which is the Potomac with a view of Alexandr[i]a. The court around is romantic but . . . wild.” Made of porous Virginia sandstone, the “castle” was sealed with a mixture of ground limestone, salt, ground rice, and glue that produced an illusion of sheer whiteness. It was twice as large as the Quincy meetinghouse, though no single room was finished and thirteen fires had to be fed day and night to fend off the autumn cold.

Because there were no stores nearby, you had to travel a mile through pathless mud to George Town, “the very dirtyest Hole I ever saw,” just to go marketing. Despite the abundance of trees, firewood was scarce because no woodcutters could be found south of Philadelphia. Bell installers were similarly elusive, so you had to walk great distances to communicate with a husband two floors above or a servant at the opposite end of the house. The whole mansion was damp, and the large reception hall on the first floor was fit only to hang laundry. But an oval space upstairs, designed to replicate George Washington’s favorite room in the Philadelphia mansion, was filled with Abigail’s mahogany furniture and already “very handsome.” One day, under the auspices of some future President’s wife with far more money than Abigail had at her disposal, it would be sublime. For now, she was “determined to be satisfied and content, to say nothing of [the] inconvenience.” It would have had to “be a worse place than even George Town” for her to balk at a three-month stay.

Whether she stayed three months or four years, this house was not built for her but “for the ages to come,” she presciently observed, implicitly expressing a faith in America’s future, whatever she would say afterward. But even in its infanthood, it was fit for the first family of a great nation. Instead of gazing into the dark, as she had in Philadelphia, Abigail could look out from her room and see sunlit boats drifting down the Potomac as she wrote Mary in Quincy or Elizabeth in Atkinson.

Abigail was grateful she had brought her own thirteen northern servants, who were superior to any twenty slaves or former slaves employed by other statesmen’s wives. These blacks were nothing like her industrious Phoebe in Quincy. “You can form no conception of the listlessness, the indolence and apparent want of capacity for business of these [southern] black people,” she wrote her sister Elizabeth. But then, “How is it possible,” she asked, that a captive, reared with “no sort of stimulous, but their driver . . . should have any ambition?” The fault lay not with the blacks but with the pernicious institution of slavery itself.

There was no library when she arrived at the President’s House, but she found both John and William Shaw comfortably settled in partially furnished studies. John was as well as possible, considering that Alexander Hamilton had a month before disseminated a fifty-four-page rant, impugning the President’s judgment and even sanity and urging Federalists to shun him and vote for his Federalist running mate, Charles Coteworth Pinckney; though Hamilton’s long, twisted argument, quickly picked up by the newspapers, would surely benefit Jefferson more than anyone else. In days to come, Abigail would have time to contemplate the damage wrought by Hamilton’s outburst. Now, though, all political worries were overthrown by the blissful sight of a letter from the Cranches, where her sister Mary gave proof that she was still living by scratching a few agitated, barely coherent lines in her unmistakable scrawl:

Welcome thou best of women, thou best of sisters, thou Kindest of Friends, the soother of ever[y] woe to the city of Washington . . . Take their sweet offspring to your benevolent Bosom and say to them Thus would your grandmama do if she could hold you in her arms. I tremble, I can scarcly hold my pen. Others must tell you how I am afflicted with Boils, forty upon my back . . . More would [I write] if I had strength to—